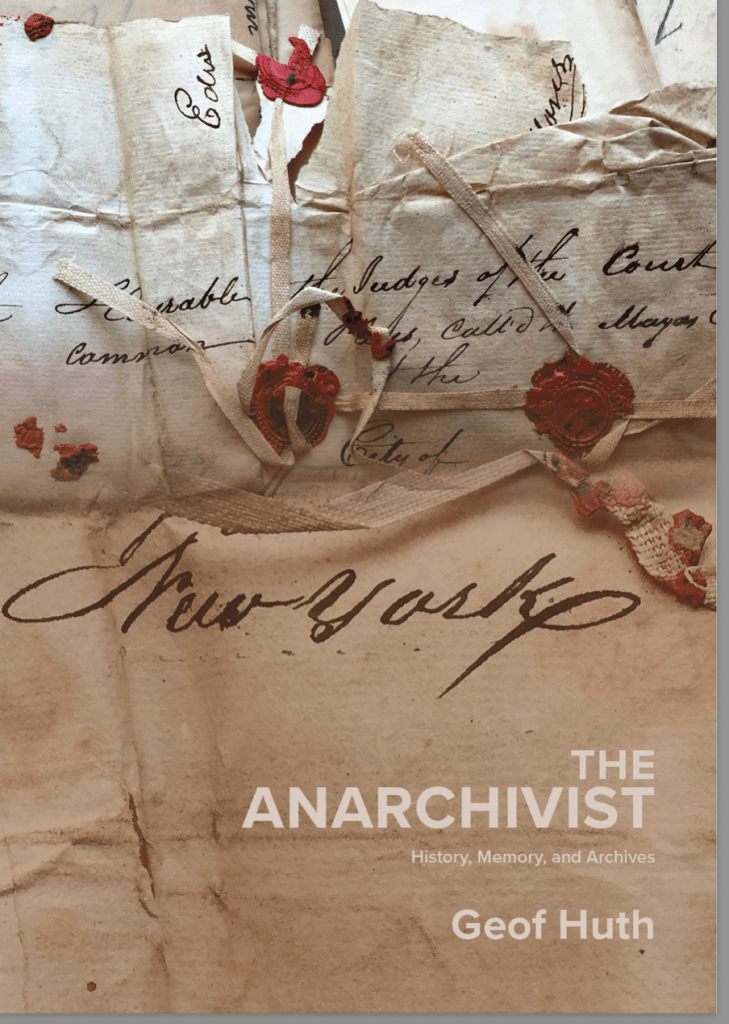

An essay by Geof Huth from his book, The Anarchist: History, Memory, and Archives (AC Books, 2020).

“Records as Opposed to Archives as Opposed to Records,” an essay by Geof Huth from his book The Anarchist: History, Memory, and Archives (AC Books, 2020). With permission of the author.

At its deepest, most fundamental level, archives assumes a genuine faith in humanity, a faith that there will be a future and generations to which archives will matter.

Scott Cline, “‘To the Limit of Our Integrity’: Reflections on Archival Being,” The American Archivist 72:2 (Fall/Winter 2009): 334.

Records are not naturally archival. Only human intervention in the form of a decision transforms records into archives. And human intervention can also reverse that decision. Just as we appraise records, we can reappraise them.

The archivist,[i] however, starts within a state of nothingness. Or each archivist’s entire universe of documentation lies before them, even if as-yet-unknown, even if likely not wholly knowable. The various universes an archivist might encounter differ. One archivist may have the sole responsibility of managing the records of their own institution; another may be required to acquire those pure archives and, in addition, collect records documenting multiple aspects of human activity—as well as rare books and ephemera. The world may be finite, but the possibilities within it are infinite.

Deciding what records may be honored with the designation “archival” begins with the assumptions and biases rattling inside the archivist’s head. We cannot escape our preconceptions, so we must control them, by dint of will. For instance, most archivists likely believe that age is one marker of archives; if a record is old, then it is archival—or, at least, likely so. In this syllogism,[ii] we accept that records of any slice of the past are less abundant than records today, then we posit that the relative paucity of records suggests that that era is likely not documented to the degree to which our own age is, and thus we conclude that we must save the record to ensure we have retained reasonably robust documentation of that past.

The problem with syllogism is it requires us to make assumptions that lead us to a destination that may not be the correct one. The constant problem with this logical formulation is that it begins with assumptions (two premises), which may or may not be true—even as they are believed to be. Equating age with value tricks us into ignoring, at least to a degree, the data in the record itself. Since we are nearing a century since archivists began announcing we have too many records to manage reasonably, we need to be skeptical about easy answers to appraisal conundrums.[iii] I have sat in appraisal meetings arguing with colleagues that records from the 1940s do not constitute records of archival value merely because of their date of creation. We must always focus on the value of the records’ data. The planet can lose metric tons of records from the 1940s and still retain a reasonable level of documentation of humanity. We simply do not need everything.

Regardless of the level of intellectual rigor and procedural precision we might employ, any attempt at appraisal is a crap shoot. Appraisal is the act of determining today the value of parts of yesterday to the world come tomorrow. Appraisal is an act of faith and futurism. We imagine a future in which these records under consideration still exist, and we consider if people will use them frequently and deeply enough to justify their continued existence. And how do we determine the needs of the future? By extrapolating based on the use of such records today and by trying to imagine new uses that could be made of these records.

Yet what the past tells us most clearly is that our assumptions about the future are often incorrect. We may over- or underestimate use. New ideas for using records will appear in the future, and the volume of these new ideas will always exceed archivists’ imaginations about such use—because we are always out- numbered by the quantity of potential users, and because we are generally not using the records ourselves. We did not imagine the data-heavy uses of records often made today. We did not conceive of historians collecting masses of un- structured data that they would then give structure to, thus creating richer ways to understand the past. We did not imagine the computer age. We did not conceive of studying all the records—held by multiple repositories and government agencies—about the female head librarians of the branch libraries of New York Public Library to create a rich social history of those women.

Actually, one of us did imagine the last of these[iv] because that is the focus of the research of Bob Sink, formerly the institutional archivist of the New York Public Library, and now retired. Archivists themselves can be researchers, and in being such they can imagine new uses of records, but having all archivists be researchers is unlikely to improve appraisal decisions. First, we will still be individual humans thinking in our own ways; we will not gain the imaginations of all potential researchers just by being one ourselves. The real issue is even deeper. Most research cannot take place in but a single repository. Just as the universe of records is bigger than any one archives can manage, so the universe of a single research project almost always exceeds the range of a single repository.

That is why the archivist must always be an existentialist when it comes to appraisal: “I can’t appraise records. I’ll appraise records.”[v] “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”[vi] We have to accept the likelihood of failure without being consumed by despair.

Archival appraisal is an audacious act. When appraising, we make decisions about matters of life and death (though only for records). We transform a mere record—a concretized set of data documenting purported facts—into an archive. We designate a record to become part of that most exalted category of record: archival, and thus permanent. Because of the power permanence asserts on the future and the cost of that permanence to our organizations, we must do this carefully to justify our decisions.

Yet our decisions may not always stand. The sad truth about appraisal is that others may undo our conclusion. A record one person marked as archival may become something else: a record to discard, a record to transfer to another organization, a record to sell. Those who come after us may symbolically countersign our appraisal reports—or tear them up. An archival record today may become non-archival tomorrow.

One reason for this is that other archivists come to different conclusions about the records. Another is that the circumstances and facts that guided the original decision have changed. When an archives begins to run out of space—when space becomes more precious—the records themselves must demonstrate their value even more clearly. Archives, you see, are archives only in certain contexts; if the context changes, then the value of the record also fluctuates—up, down, or even sideways. A little acknowledged truth is that no record is purely archival. No record is archival in any contexts. A record that is archival to one repository has no archival value in another.

Take the case of the journals of Lewis and Clark on their explorations across the North American continent. Given the historical import of their work and the findings they revealed to most of the world—though definitely not all—you might assume that these records are simply and purely archival. But that cannot be the case. A record is archival only in the context in which it is kept. Thus a record may have clear archival value in an abstract sense, yet have no concrete archival value in the context of most repositories. If, for instance, someone approached a business archives and asked the archivist there if they would care to acquire the original journals of Lewis and Clark, they would likely turn away the offer, because the records would have no archival value in their corporate context. Just as records carry meaning because of the context of their creation and later use, records carry archival value in the context of the archives assessing that value.

Also, appraisal is always a process of subjective analysis. We can, and certainly should, create objective criteria to guide our appraisal decisions—measurable criteria created to make sense in the context of our specific archives—but subjectivity is unavoidable. And objectivity is often litigated rather than affirmed by subsequent archivists. I see every archivist as a sturdy link in a never-ending chain, one connected to the next as each of us assumes the responsibility from a predecessor and then transfers that responsibility to a successor. A break in the chain (via subpar storage, theft, a disaster, or even outright abandonment of the archives) can eliminate a record or set of records forever—so we usually work assiduously to ensure the protection of our archives. But sometimes we do not, because some- times we are the link in the chain that disagrees with all the preceding links.

This fact underlines the subjectivity of archives. We don’t always agree with each other’s appraisal decisions, which is good. Disagreement leads to discussion (in the best of cases), which leads to better and more nuanced decisions. This has been true in most of my appraisal work, which almost always included multiple people evaluating individual series or fonds of records and arguing about whether they were archival—and to what degree they were. My experience, however, was synchronic: five or six people sat around a table and debated the analysis one of us had written.

When we decide to veto a decision of a predecessor, our argument is with an absent past. We make the decision based on current thinking and conditions— the latter often having to do with the value of shelf space as compared to the value of the records resting thereon. In such reappraisals, we question past decisions, consider them in our current context, and decide if decisions of the past still hold true for the future.

Often enough, we rescind the archival imprimatur given to the records—but only as they relate to us in our environment. After transforming archives back into mere records, we often do something counterintuitive: we search for archives where these records may become archival again. We try to transform something that was once a mere record and then an archive and once again a record back into an archive. We struggle for redemption—because we believe there still may exist a sliver of value for the record, a corner of humanity where it is indeed an archive.

Notes:

[i] In this case, I mean the good appraisal archivist who examines a body of records without a conceived idea of how the appraisal will turn out. In appraisal, though, we almost always have the sense that the records may be archival—otherwise, we would have to carry out formal archival appraisals for each series of records created within our realm, no matter how obviously mundane and inutile each was.

[ii] When I first wrote this opening phrase, I ended it with solecism, which seemed definitely incorrect. Then I changed it to solipsism, and it was as if I, the archivist, had been transformed into a state of nothingness. Finally, I recalled syllogism. The human mind—bursting with so much information that it sheds torrents of it daily—can trick itself into believing something is factual without ever finding a fact to support that conclusion.

[iii] I desperately wanted to say conundra here (because of that untrue plural’s goofiness in English), but conundrum is not even a Latin word. Etymologists believe it was a joke word created to approximate a term in Latin. [“conundrum, n.”. OED Online. December 2018. Oxford University Press. http://www.oed.com.dbgateway.nysed.gov/view/Entry/40646?re- directedFrom =conundrum (accessed January 17, 2019).]

[iv] Bob Sink, “Episode 51: I Guess I Was Good at Osmosis,” An Archivist’s Tale (recorded 7 January 2019, posted 9 February 2019).

[v] This is a reworking of Samuel Beckett’s “I can’t go on, I’ll go on,” from the end of the 1959 novel The Unnamable. I couldn’t bear to make my version a comma splice, though.

[vi] Quoting directly here from Samuel Beckett’s 1983 short story “Worstword Ho,” which I have not read in decades.