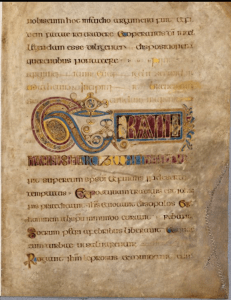

This poem takes us into Trinity College Library, describing a vaulted room filled with one million books. We also see through the poet the twelfth-century Book of Kells and recall those words of Rare Book and Manuscript librarians as well as writers like Logan in awe of the pigments illustrating beasts and letters. What a privilege it seems to have yet this book, beloved by James Joyce, alongside us, the readers. Logan lets us also consider the hidden book, “stolen for a while,” then found “stuffed beneath the sod.” As workers among such materials, we remember other materials taken away, returned in fragments: some from the Timbuktu manuscripts, the Mozart score found in the Jean Remy library in Nantes, and others.

Evocative also is Logan’s ending: Ah, friend. He allows us to meet in a reading room, picturing ourselves, our “heavens” and “hells.” But we also have in our minds all those magnificent and earthy and sometimes destructive colors of the monks in their manuscripts—a richness in knowledge.

Fol. 13r, From the Book of Kells, Trinity College. Image in the Public Domain

AND NOW, the poem

THE LIBRARY, a subsection of a “Dublin Suite: Homage to James Joyce” by John Logan

This massive, carved medieval harp of Irish oak

no longer sounds in the winds from ancient times gone

out

of Celtic towns. It rests in the long, high vaulted room

filled up with one million books whose pages chronicle

the works and ages both in our land and in Ireland.

For a hundred years no student has been here above

those huge, leather volumes that burgeon on the balconies

like matched and stacked rows of great pipes

for the unplayed organ of this magnificent place.

But both pipes and harp seem still to come alive and turn

Trinity College Library

into a fantastic temple when we stand over

the twelfth century Book of Kells,

which James Joyce so loved he carried a facsimile

to Zurich, Rome, Trieste. “It is, “

he said to friends, “the most purely Irish thing we have.

You can compare much of my work

to the intricate illuminations of this book.”

Its goat skin pages open up for us under glass

in a wooden case. At this place:

a dog nips its tail in its mouth,

but this dog is of ultramarine, most expensive

pigment after gold, for it was ground out of lapis,

and the tail of the lemon yellow orpriment.

Other figures are verdigris, folium or woad—

the verdigris, made with copper,

was mixed with vinegar, which ate into the vellum

and showed through on the reverse page.

Through the text’s pages turn constant, colored arabesques

of animated initial

letters—made of the bent bodies

of fabulous, elongated beasts

linked and feeding beautifully upon each other,

or upon themselves. Why, even the indigo-haired

young man gnaws at his own entrails.

The archetypal figure of the uroboros

recurs, as does that the Japanese call tomoi:

a circle divided by three arcs from its center.

These illuminations around

the Irish Script of the Gospels

are some of them benign and some terrible like that

Satan from the four temptations:

The devil is black, a skeleton with flaming hair

and short, crumpled emaciated wings, which appear

to be charred as are the bony feet—

and the reptile with such gentle

eyes is colored kermes (compounded from the dried

bodies

of female ants that die bright red).

The covers of jewels and gold are gone from the Book,

stolen for a while from the Kells

Monastery in County Meath

and then found, some of its gorgeous pages cut apart

and the whole stuffed beneath the sod.

These designs were all gestures of the bold minds of

monks—

their devils still whirring about their ears while angels

blasted their inner eyes with colors not in any

spectrum, and moaning, primitive Celtic gods still cast

up out of their hermetic interior lives strange figures

which we can all recognize as

fragments of our inhuman dreams:

all this is emblazoned here in the unimagined

and musical colors of a medieval church.

Ah, friend, look how this Book of Kells

pictures all our heavens, all our hells.

From Logan’s book, The Bridge of Change (BOA Editions, Ltd). With permission from BOA Editions.